by A.E. Osworth

One can never prepare for everything.

Despite what scouting organizations may have told me growing up, with all the permutations of “be prepared” in their rules and mottos, the lesson I learn over and over again as I age and participate more widely in my community is that it is simply not possible. One can and should prepare, but it isn’t at all possible to prepare for everything.

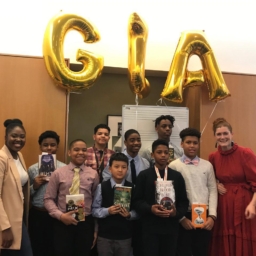

Back in 2016, my colleague Catherine Bloomer and I were asked to be the inaugural WriteOn Fellows and to head into the classroom at George Jackson Academy to teach what was then a creative writing club and what would become the creative writing elective offered during the school day. Mostly we accomplished this through a combination of listening to our students wants and needs and improvising, hammering out a curriculum and lesson plans by the seat of our pants. While this was a fun and flexible way to create an innovative learning environment, I can’t say I exactly recommend it as a long-term solution. For one thing, it’s stressful to do, and for another, it doesn’t allow for the explication of intricacies and connections in writing, except for those that arise entirely by chance. But as I became Education Director for WriteOn, I was mostly concerned with a simple truth: it isn’t replicable. In teaching the Fellows their orientation, I managed to distill what Catherine and I had been naturally doing into a series of steps: Introduction (usually a game to sneakily emphasize a take-away idea), Information (usually in the form of a reading or a discussion or both), Implementation (a framework for trying out some of the tools exemplified in a reading or other creative piece) and Introspection (a way to evaluate, with a group and by oneself, if the foray into writing that day has accomplished what the young author set out to do, essentially the same workshopping graduate students in creative writing engage in). Ah yes, I thought to myself, now the Fellows will be prepared to go into the classroom.

But life does not work that way. Learning a basic formula is never the extent of a master class. And our students and Fellows deserve a master class. As problems without easy solutions cropped up and our Fellows had questions and brand new ideas they wanted to try, it became more apparent that the stand-and-deliver method of teaching would not work for our Fellows anymore than it works for the middle school students they were instructing. After all, Catherine and I had the opportunity to try as many new ideas as we wanted; why should it be different for those who come after? It was time to think as deeply about how we were teaching our Fellows as we were thinking about how to teach our middle schoolers.

Catherine Bloomer signed on as Director of Research and Publications (now Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment Director), and together we developed and continue to develop a method of teaching our Fellows that emphasizes the same freedom we enjoyed while also making sure they’re well-prepared to enter the classroom. And while that method has many components, perhaps the most meaningful is progressing from a preparation-only method to a support method. What that practically entails is offering a bi-weekly seminar during which Fellows teaching both in the Spring and Fall semesters can help troubleshoot problems, brainstorm curriculum and lesson ideas, and role-play practice sessions to try new and exciting exercises before they’re deployed in the classroom. Instead of providing a framework and expecting students to navigate what is, for some, their first time in a classroom of their own, we instead deliver the same preparatory method and then continue to check in as a group, gleaning the same sort of peer learning benefits graduate students receive in a writing workshop, but applied to pedagogy and classroom management. The art of teaching is just as important as the art of writing.

Along the way, we also support Fellows in a deeper dive, by offering a survey of feminist pedagogical theory, and help guide Fellows in aspects of professional life unique to both writers and teachers—the authoring of teaching statements, for example. All exercises that continue to ask the question—how do we teach art? And what does success look like when we do? Instead of prescribing the answers, as a preparation-only model might, a support model allows students to figure out those answers for themselves.